Coming Into Kindness: The Quiet Power of Payne’s The Holdover’s

By Polly Buckley

ENTERTAINMENT

Edited by Cece Wilson

12/7/20254 min read

The Holdovers is more than a coming-of-age film; it’s a poignant study in compassion that unfolds through the lives of three outcasts shaped by grief and grievance alike. Set against a backdrop of loneliness and unexpected connection, the film reminds us that growing up isn’t entirely about ambition or self-discovery – it is, in equal parts, about kindness and finding the courage to give that very kindness to others, and in turn, potentially more difficult parts of ourselves. Blending the sensibilities of a coming-of-age story, a road movie and a holiday dramedy, The Holdovers draws its quiet power from its humanity – from the way it illustrates that bleakness, disappointment and isolation can give rise to a community grounded in empathy and understanding.

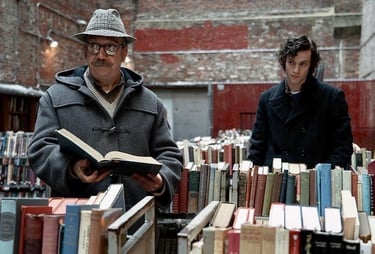

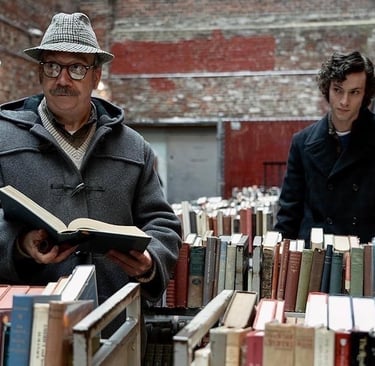

Set in the make-believe New England boarding school Barton Academy, The Holdovers revolves around Professor Hunham, the school’s cantankerous yet disarmingly tender Ancient History teacher, who is left with the onerous task of looking after 1970/1971’s Christmas “holdovers”. Quickly, these holdovers dwindle in number as many leave to go on a ski trip with one of the wealthiest boys’ fathers, leaving Angus – who can’t reach his mother to gain permission to leave – in the unyielding hands of Hunham and the warm embrace of Mary Lamb, the school’s cook, who has recently lost her son to the Vietnam War.

But Payne’s story is less about plot than presence; its focus is the gradual thaw between three people who have every reason to remain closed off. Harbouring more than just teenage angst, we learn that Angus’s father is institutionalised when the trio head to Boston, with Mary departing to see her sister. Through patience, attention and empathy, a quiet sense of community forms between the three – most unexpectedly between Hunham and Angus – and it becomes the emotional backbone of the film. The narrative resolves with Hunham protecting Angus from expulsion while Mary steadies him under the shadow of military school and a potential conscription to the Vietnam War. When they part – Hunham on the road, now jobless by choice but quietly triumphant; Mary back at work; Angus towards college – their fragile community has served its purpose. Coming of age, or rather coming into kindness, the oddballs – the people carrying invisible burdens – carry each other into their next chapter of life. How Payne gets us there – from hostility to tenderness – is where the film truly shines.

Angus is, very understandably, angry – furious even – at the cards he has been dealt this year. He takes this out on Hunham and, like any teenager would, finds Hunham’s clumsy attempts at making Christmas fun pathetic instead of endearing. The two are immediately at odds, their dynamic reflecting the parenting style of the film’s 1970s setting. In this, the film becomes an eloquent study of masculinity across generations. Parenting in this period – far removed from today’s gentler, emotionally literate ideals – was defined by discipline, restraint and authority. Emotional expression was often seen as weakness, and rebellion, whether in art, music or behaviour, as something to suppress. Hunham embodies this outdated ideal: rigid, principled and profoundly uncomfortable with vulnerability. To Angus, he appears fossilised – a man who has never left Barton, as ancient as the texts he teaches. There’s no doubt Hunham comes across as a man who’s given up; his half-hearted attempts to connect with others – like when he obliviously makes a crude joke about masturbation to a colleague mourning his mother – say enough about his inability to relate to his peers, let alone his students.

Angus warms more easily to Mary, who is almost maternal in her approach to him, in that she sees what he is missing: understanding, kindness and empathy. Mary offers what Angus and Hunham lack – a maternal gentleness, a gift for soothing pain, a philosophy carved out of grief and grounded in acceptance. The film’s celebration of femininity emerges through Mary, whose compassion for Angus is as much an act of self-preservation as it is of nurture – a way of reasserting care in a world that has taken it from her. Her community with Hunham is different; she affords him further judgment, by nature that they are nearer in age, but sees and seeks to comfort his melancholic, hard-edged talent for solitude, which she is certainly also able to locate within herself. Between Mary and Hunham, community, actually, comes quite easily; they share whiskey, allow Mary’s grief to breathe, and give Hunham room to talk about his interests. They by no means appear as friends, but there is a gentle care for one another, evidenced in their tender dialogue and formed by their mutual grief, bleak philosophy, and deeply concealed desire to be happier and yearn for empathetic community.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it takes quite a catastrophic moment to bring together Angus and Hunham. In the film’s first act, Angus and Hunham’s quarrel reaches its peak when Hunham catches Angus on the phone attempting to book a hotel room after lying about needing to use the toilet. What follows is a charmingly witty sequence of Angus running away from Hunham, chanting his own exercise rhetoric back at him, while Hunham struggles to catch up. This scene, however, comes to an abrupt halt when their interaction peaks – Angus pole vaults, having reached the school’s out-of-bounds gym, and painfully dislocates his shoulder.

The Holdovers’ quiet power lies not in grand transformation but in small acts of grace – in the way care, however awkward or imperfect, becomes a bridge between isolation and understanding. Payne resists sentimentality, choosing instead to illuminate the tenderness that can grow out of disappointment and defeat. Hunham, Mary and Angus may part ways, but the care they learn to give and receive lingers beyond Barton’s snowy walls. In the end, The Holdovers reminds us that coming of age is less about growing up than about growing gentler – finding, even in our loneliest seasons, the courage to come into kindness.

©Pinterest, Miramax

For more, explore fashion, travel, and lifestyle insights here.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

info@femmine.co.uk